An investor once shared with me a simple framework for the fundamental skills of venture capital:

- 👁 See (the deal)

- 🧠 Analyze (the deal)

- ❤️ Win (the deal)

Success in VC demands all three. But that doesn’t mean they're equally important.

An investor once shared with me a simple framework for the fundamental skills of venture capital:

Success in VC demands all three. But that doesn’t mean they're equally important.

Long-form essays on the economics of tech, with the data to back it up. All signal, no noise.

Read by 5,000+ founders, engineers, and investors.

You can’t analyze a deal you can't see. You also can’t win a deal you can't see.

“Seeing the deal,” also referred to as “deal flow,” continues to be an important differentiator between the best funds and the rest of the pack.

Networks and access are a potent currency in Silicon Valley. As I like to say: you can be the smartest person in the room, but if you aren’t even in the room, it doesn’t matter.

As such, VC firms want to know about every deal being done, even if they have little interest in doing the deal. They want the option to say no. As in many domains, that optionality is incredibly valuable.

But simple awareness of a fundraise does not do much for you as a VC. These days, it’s often common knowledge that a particular company is fundraising.

Even if you know a deal is going down, there’s no guarantee you will be able to insert yourself into the consideration set of potential partners. I’ve had entrepreneurs directly deny to me they were fundraising when they in fact were, only to admit it after the fundraise announced shortly thereafter.

The concept of an "anti-portfolio" proves that even if you see a deal you can still drop the ball.

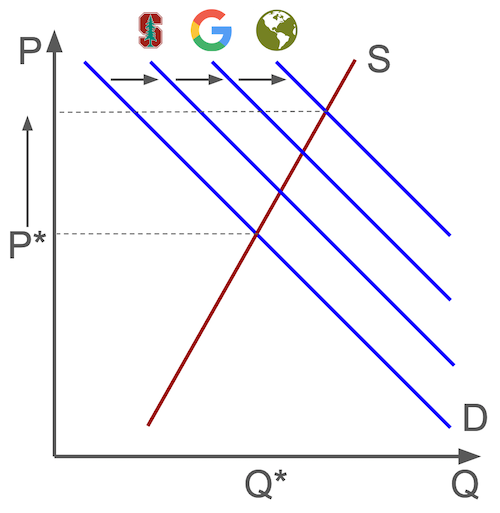

Many VCs "saw" the Facebook deal. Many VCs "saw" the Google deal. And yet they missed the most explosive growth companies the world has ever seen.

"Seeing" is necessary but not sufficient.

VC's have always relied on the strength of their networks for dealflow.

As an increasing number of founders come from more diverse backgrounds, VC's will have to change to stay relevant.

More diverse partnerships, more openness towards cold emails, less pattern matching.

— Boris Wertz (@bwertz) August 20, 2019

I don't mean to deny or discount the value of deal flow. Deal flow is a valuable resource, but it's exactly that — a resource. A resource must be extracted, enriched, and processed. Converting that resource into useful energy requires investment and effort. Otherwise, it remains inert.

Venture capitalists often talk about “pattern matching.” After years of investing and watching startups succeed or fail, VCs supposedly develop a keen sense of what drives success, detecting signals in the noise. These signals can take many forms, but the important claims are:

Pattern matching epitomizes the “analyze” skill.

There are three issues with basing your competitive advantage on pattern matching.

First, pattern matching is rarely differentiated. The important metrics and signs of traction are well-known these days. Increasingly, the “good” founders are obvious — those with the best pedigrees or past successes.

Like in public equities, obvious patterns are priced in. If it’s not priced in — most often — it’s not a real pattern.

This dilutes the value of pattern matching. Suddenly, the well-worn patterns VCs rely on so heavily begin to work against them:

In a competitive environment, patterns carry the seeds of their own impotence.

Second, it’s not at all obvious that pattern matching even helps much at the earliest stage. The drivers of success are indeterminate, and stories abound about ideas that seemed dumb at first but became winners. In some cases, even the VCs who funded the best companies had serious doubts going in.

If even the “smartest guys in the room” are not that smart, we know we have a problem.

VC pattern matching and startup folklore are the path to mediocrity. Focus on commercial success and let data tell the story. You’ll be the next pattern people try to match. https://t.co/ggDZJmJWbV

— bradford cross (@bradfordcross) September 22, 2018

Third, this all assumes the patterns are correct — that they contain some useful information.

This too is suspect.

Data in VC is notoriously spotty, unreliable, and often unavailable entirely. Tying cause to effect is quite difficult, and success or failure is often over-determined.

In this environment, our natural tendency as humans is to fall back on heuristics. Some of these are helpful, but many are problematic.

Another word for a problematic heuristic is bias.

"There’s quite substantial unconscious bias that most of my male investment colleagues don’t see, where if a guy looks and smells the part with the pattern matching, (he) just (gets) such a break" – Linden Rhoads, General Manager of the W Fund (Source)

“Pattern matching” seems increasingly tenuous. Either it’s easy and reliable, in which case it gets priced in, or it’s difficult to execute on in practice, making it easy to fool oneself into believing non-existent patterns, almost superstitiously.

Either way, it’s fraught.

Venture capital is a match making service.

Winning in modern venture investing fundamentally concerns what I call “people matching” — bringing together the right combination of founders and investors to partner on a particular startup or idea.

It’s about the people, not the capital. Yes, capital is also matched or allocated to specific startups, but this function is being commoditized.

Showing up with a checkbook today is no longer cool or particularly notable.

Not all funds can show up with the right partner, however. A partner the entrepreneur wants to work with. Someone who will make both the founder and the startup better by their presence and involvement.

In this sense, the coveted “partner” title is actually quite fitting.

Partners partner.

In this model, venture capital firms are less allocators of capital — which is currently cheap, plentiful, and most importantly, homogeneous — and more allocators of people, who remain differentiated even in this hot house environment.

People are the truly limited and differentiated resource of VC firms. General Partners seek to maximize the capacity of the fund to generate returns for its Limited Partners, but ironically, it is the General Partners who are “limited” — there’s only so many of them, and they must be deployed judiciously. And with all the capital flowing around these days, Limited Partners are increasingly unlimited.

Unlike a publicly traded company, which can effectively absorb any amount of capital the market could realistically desire to invest, with prices regulating this flow, the typical startup cannot and does not want to take on every possible dollar from every willing investor. The best deals are often oversubscribed multiple times over. Financing rounds are rivalrous — we can’t all do the deal.

The VC who can most quickly convince a founder that they are the right person to partner with will win the deal. And by winning the deal, others, by definition, lose the deal.

Talking to 43+ funds is a massive waste of time of everyone’s time

Now that access is completely commoditized, closing is the most valuable skill

Founders, find your lead first to remove noise & get back to work

If it’s unclear what value a participating firm offers, move on. https://t.co/o4zbodpENL

— Brianne Kimmel (@briannekimmel) December 3, 2019

Winning is therefore the fulcrum upon which success in venture turns. Two comparable firms can both see the deal, analyze the deal “correctly”, and yet only one may win the deal in the end. The firm that does a better job of people matching will, in the end, triumph.

This is why winning matters so much.

Venture capital is evolving from a game of picking winners to a game of being picked by winners.

Authentic relationships and credible ability to add value matter more than ever.

Venture capital is no longer where one goes to retire quietly after an illustrious operating career. It’s where one goes to hustle.

Pushing to win an investment I really want. Might lose it.

Founder in driver's seat. Some investors complain, I love it. Some call this a bubble, but everyone is being rational.

Founder/investor dynamic is reaching equilibrium and this is how it should be.

— Paul Murphy (@paulbz) November 19, 2019

I think this is a positive trend, encouraging deeper empathy between investors and founders. If anything, bringing VCs down a peg might humanize them — the gilded kings and queens of Silicon Valley become the humble servants of entrepreneurs.

There’s some moral justice in this. I’ve always been irked by the very different lives lived by founders and their investors:

This is out of balance. Entrepreneurs hustle, why shouldn't VCs?

Long-form essays on the economics of tech, with the data to back it up. All signal, no noise.

Read by 5,000+ founders, engineers, and investors.