Age

Earnings peak in the late 40s

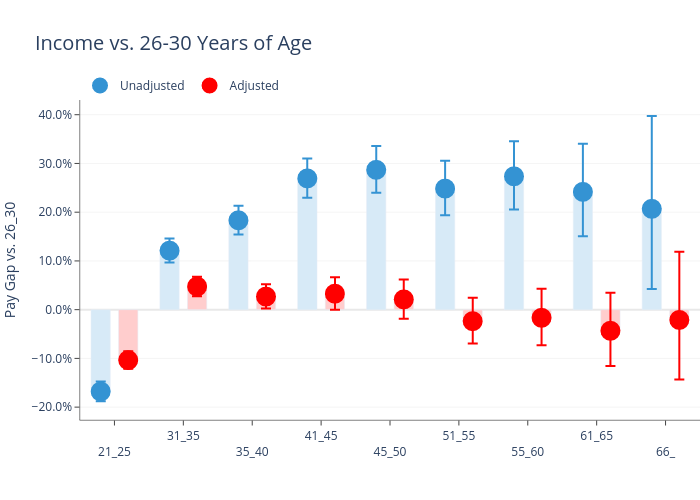

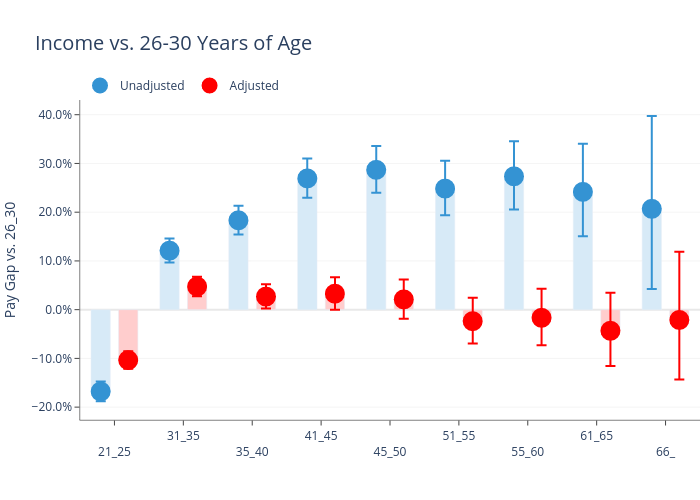

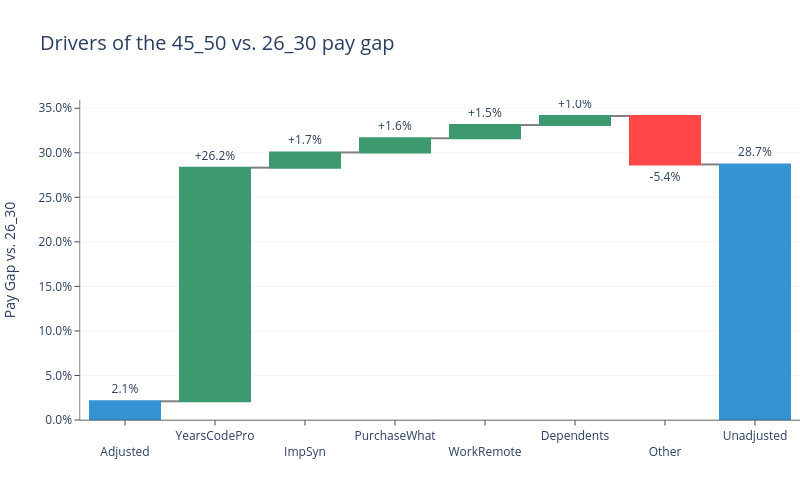

Developer earnings rise fairly steadily from the early 20s through the late 40s. The late 40s represent the highest earnings of a developer’s life, where the average developer earns 28.7% more than the typical 26-30 year old (the most common age range in the data), after which pay stabilizes before finally beginning to decline in the early 60s.

Age doesn’t matter much after 35

However, adjusting for other characteristics, age is most “advantageous” in the 31-35 range, when a developer can expect to earn 4.7% more than an equivalent developer five years their junior. This advantage is highly statistically significant.

The pay bump quickly dissipates with additional years however, losing statistical significance and even turning somewhat negative by the 51 to 55 range, though this is not precisely estimated.

The key point is that the additional income earned by older developers is entirely explained by factors unrelated to age. When we control for other factors, pay does not vary much by age after 35.

Little causal impact of age

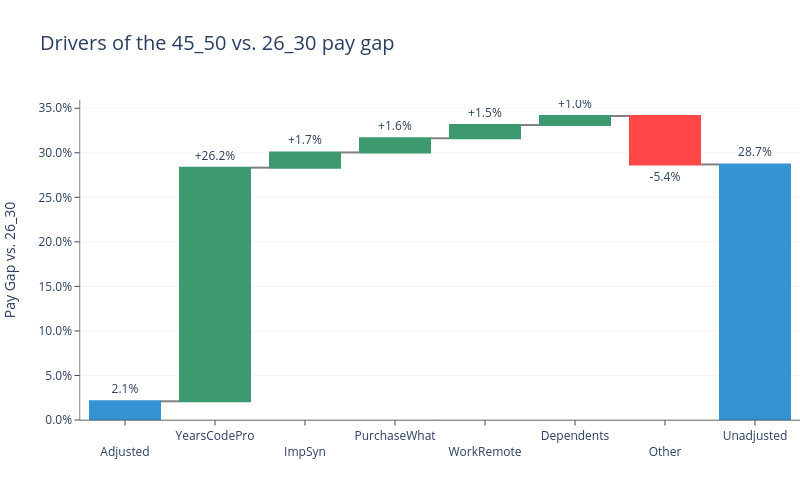

Why does the correlation between age and income disappear after controlling for other factors? Let’s dig in:

The analytics demonstrate that years of professional coding experience matters much more than age itself, which is what you’d hope to see. These additional years of professional experience effectively explain the entire earnings premium for older software engineers.

Additionally important variables include self-rated competence, having influence over technology purchases in their organization, and working remotely (which older workers are more likely to do), and having dependents.

Race

Minorities are both the highest and lowest-paid software developers

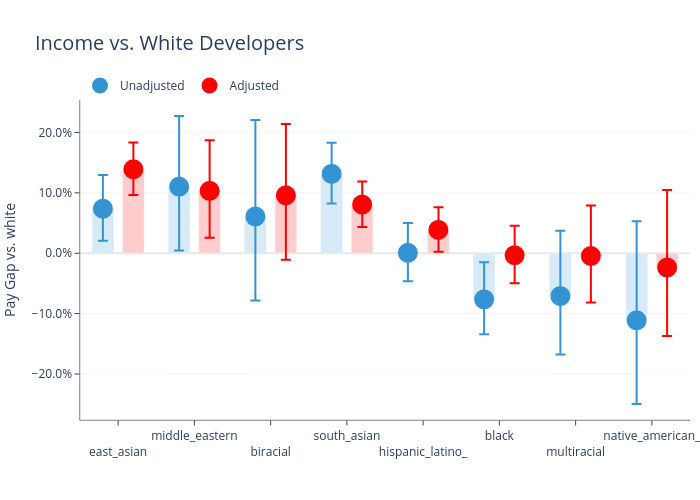

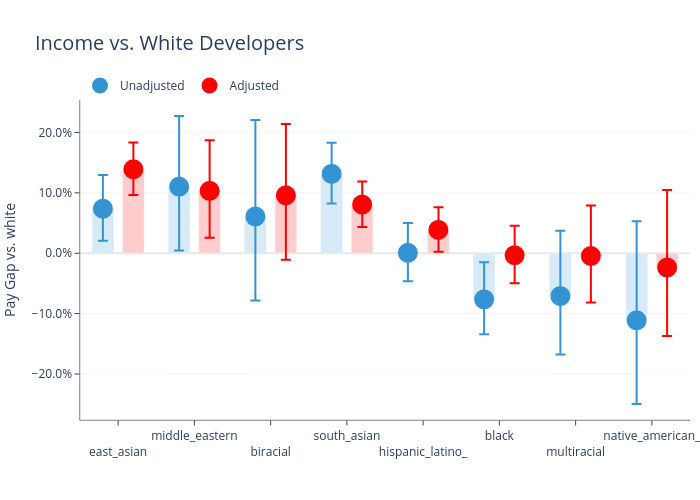

As in last year’s analysis, the largest pay gaps are between minority groups, which make up both the highest and lowest-paid developers.

East and South Asians see the most statistically significant pay premiums relative to white developers with or without controls in the regression. In the case of East Asians, their pay premium increases after controlling for various factors.

These premiums are large and meaningful — East Asians earn 7.4% more than white developers and 13.9% more controlling for observable characteristics, while South Asians earn 13.1% unadjusted and 8.1% adjusted more than whites respectively.

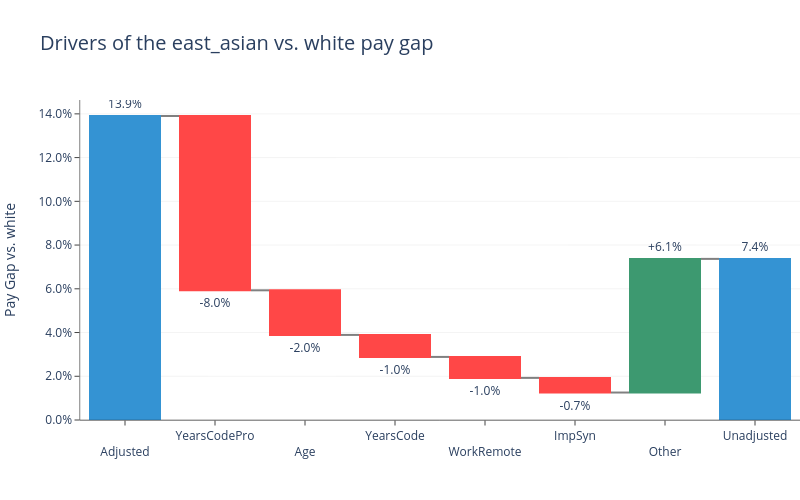

Examining the East Asian pay advantage

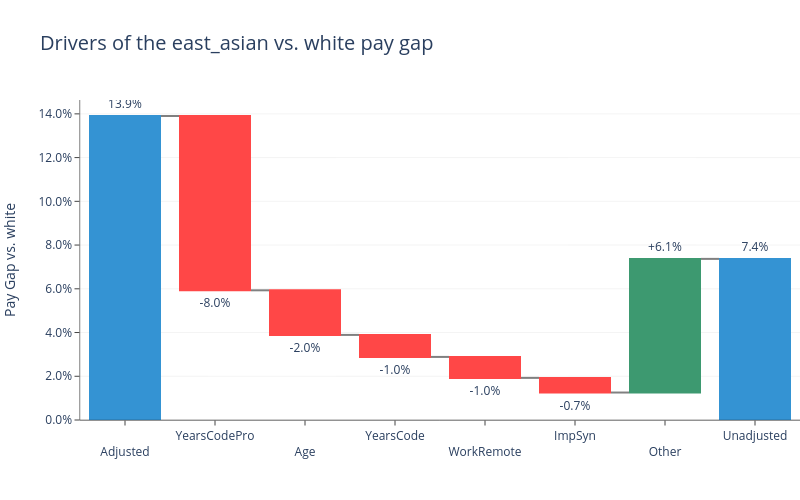

Breaking down the explainable East Asian earnings premium yields some interesting findings:

First — years of professional coding experience is far and away the biggest factor holding down the pay of East Asian software engineers. East Asian developers typically have less work experience than whites, which holds down their earnings.

- My calculations suggest that

East Asian developer would earn 8.0% more if they had similar amounts of professional experience as whites

- This rises to 9.0% if we add in additional, non-professional, coding experience.

Age also holds back East Asian developers, as they are typically younger than white developers. This amounts to a 2.0% pay disadvantage.

Lastly, the sheer magnitude of the earnings premium enjoyed by Asian developers should be noted. That the premium remains so large even after controlling for various factors is puzzling.

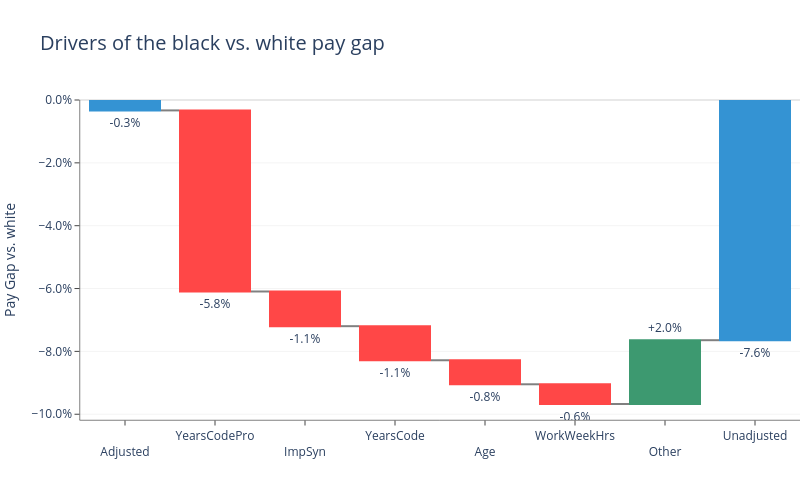

Good and bad news for black software developers

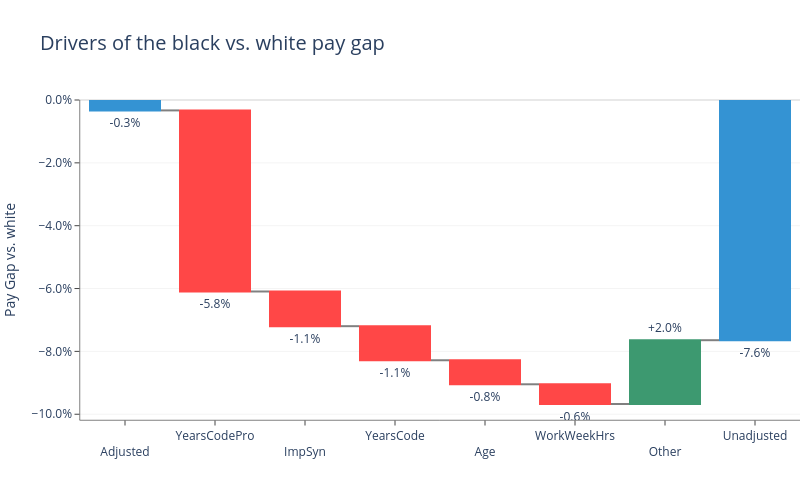

Let’s look at one more — the pay gap for black developers. The unadjusted gap — which again simply compares average earnings of black and white developers — is -7.6%, while the adjusted gap contracts meaningfully to -0.3%, which is not statistically significant:

Breaking down the explainable gap for blacks reveals similar drivers as we saw in the East Asian case. Years of professional coding experience is the main contributor to lower pay for black software engineers relative to whites, in total driving 5.8 percentage points of the overall 7.6% gap. Nothing else matters nearly as much.

In a sense, this is heartening. Assuming a black engineer gets as much out of an additional year of work experience as anyone else, purely closing the gap there would bring black pay nearly in line with white pay.

On the other hand, that the unadjusted gap is explainable via years of experience also means that the gap is unlikely to close anytime soon.

Why? The age structure of the workplace is slow to change — it takes decades to see sizable shifts

- Additionally, as the industry diversifies, by definition most

black professionals entering the software development career track start off at the bottom rung of the ladder

- Thus, the diversification of the industry in fact depresses average

black earnings, as fresh out of bootcamp developers don’t earn nearly as much as seasoned veterans

This is not a bad thing — but it does mean I can’t conclude something nefarious is behind the slow convergence of black and white wages without other evidence.

The other factor worth touching on is ImpSyn which is a variable representing a respondent’s own confidence in their skills as a software developer. More confident developers earn more, and there appears to be a confidence gap between black and white developers driving 1.1% of the earnings gap.

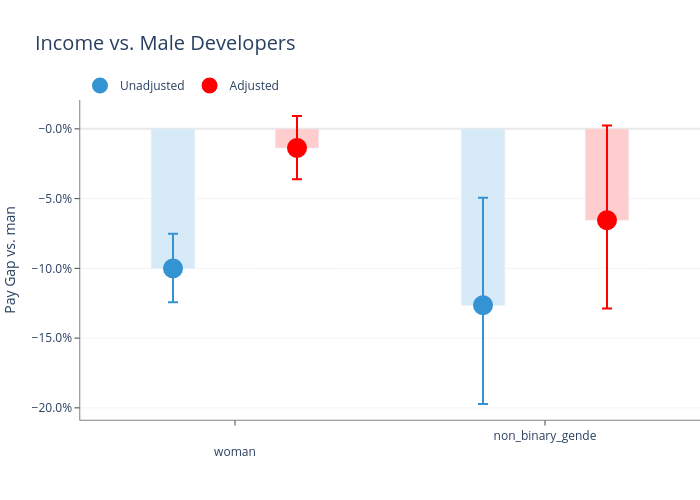

Gender

Young women entering the software development workforce pull down average female earnings

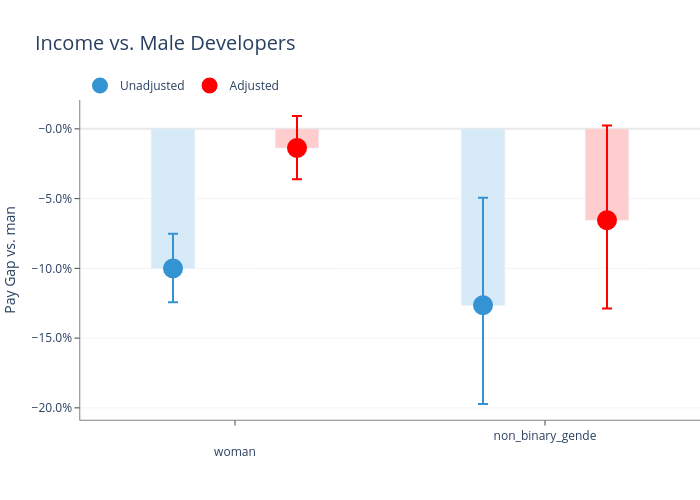

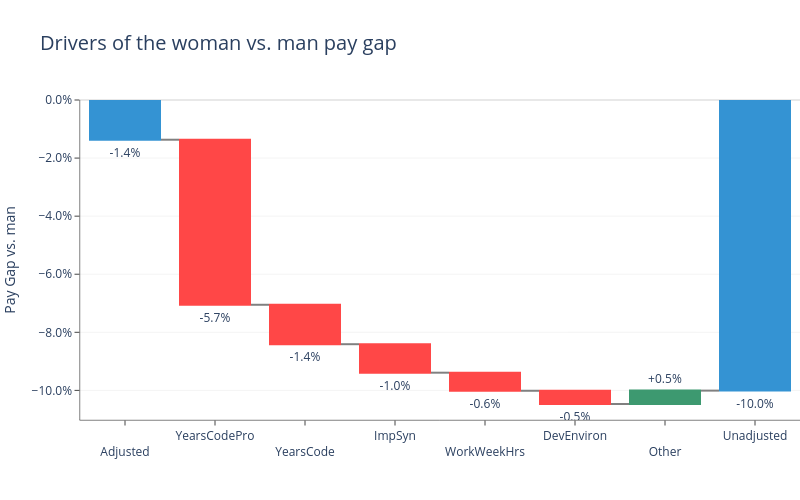

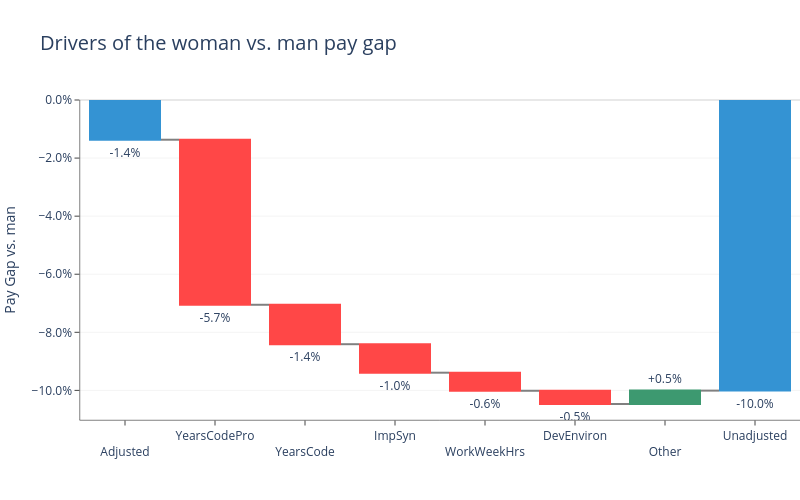

Women earn 10.0% less than male software engineers on average, a sizable difference. However, this gap is effectively eliminated once we adjust for controllable factors, falling to only 1.4%, which is not statistically significant.

In diagnosing the unadjusted 10.0% pay gap for women, years of experience pops up once again as a dominant factor explaining most of the gap:

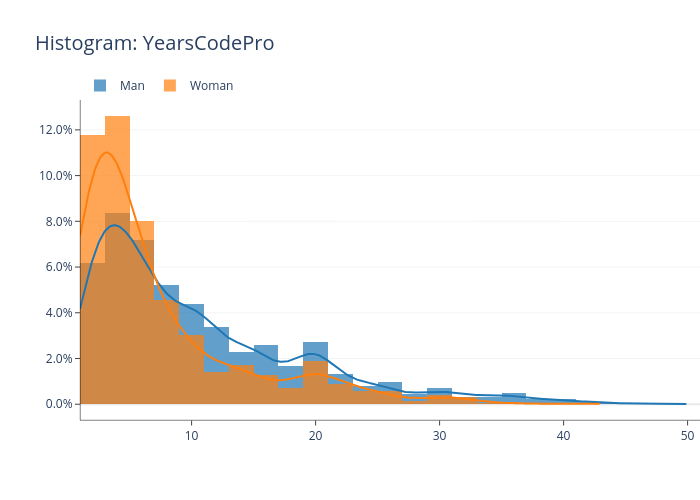

5.7 percentage points of the gender pay gap can be explained by the fact that female developers have less professional experience than male developers on average. Adding in overall coding experience explains 7.1 total percentage points of the overall gap.

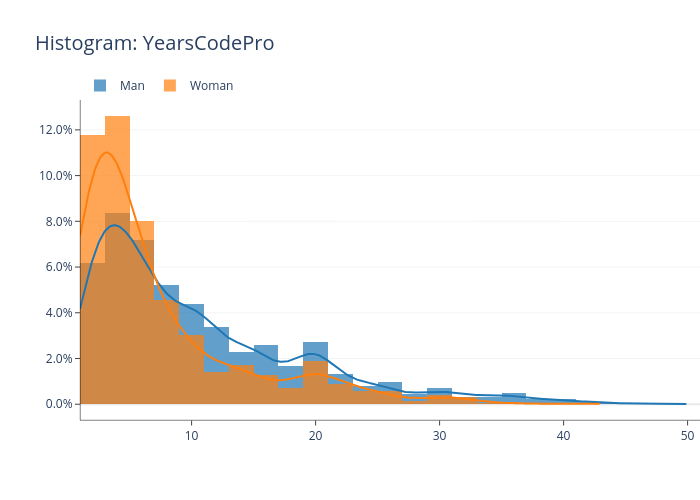

While women are only 1.7 years younger than men on average in the dataset, they have 3.3 fewer years of professional coding experience (7.1 years for women vs. 10.4 for men). We can see this in the histogram / kernel density estimation comparing the respective distributions of years of professional coding experience of men and women, where the distribution for women is shifted and more clustered to the left. This meaningful difference explains why professional experience is such as major driver of the gender wage gap.

Confidence (ImpSyn) comes up again as a factor pulling down female wages. Here, the confidence gap explains 1.0% of the overall female-male gender gap, very similar in magnitude to that of black developers vs. white developers.

Small contribution from other factors

In line with other research, women are also less confident about their own programming skills than men are (who for all we know might be overconfident), which explains another 1.0% of the total gap (because higher confidence leads to higher pay, as I cover in a later post).

Experience and confidence collectively explain 8.1% of the gender pay gap among software engineers, leaving only a 1.9% gap, including the 1.4 percentage point difference that we cannot explain.

Sexual orientation

Earnings penalty for non-straight developers disappears after controlling for other factors

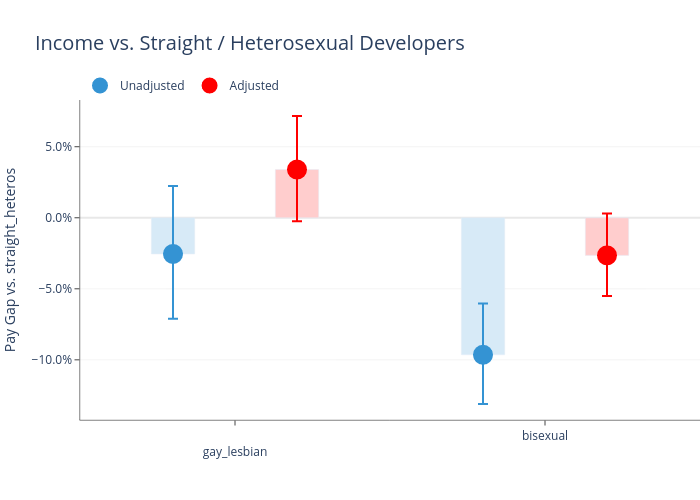

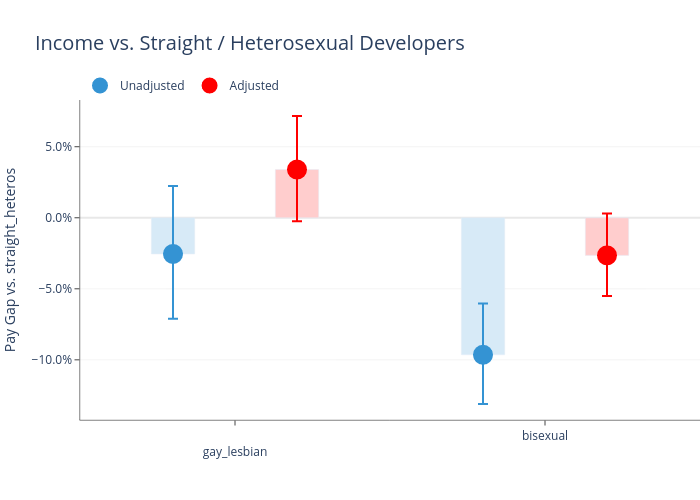

Unadjusted pay gaps among non-straight software engineers ranges from 2.5% for gay and lesbian developers to 9.6% for bisexual developers, which simply means these individuals earn less on average than straight engineers.

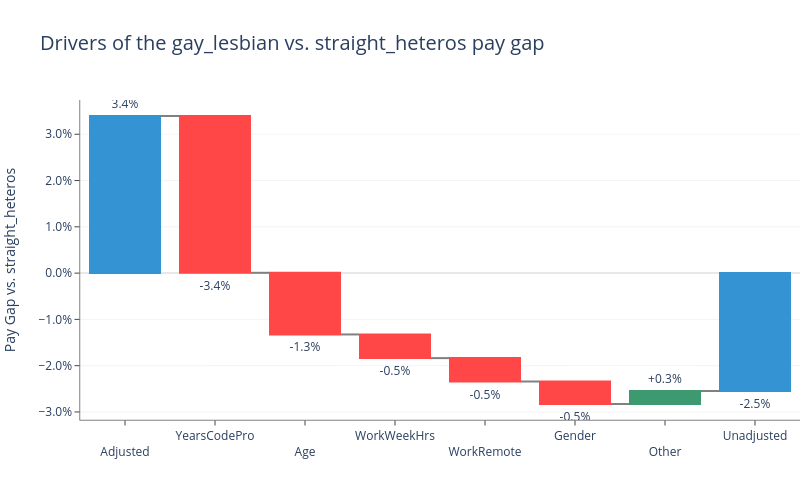

In the case of gay and lesbian developers however, this gap closes and actually reverses once I add controls. The gap becomes a pay advantage of 3.4%.

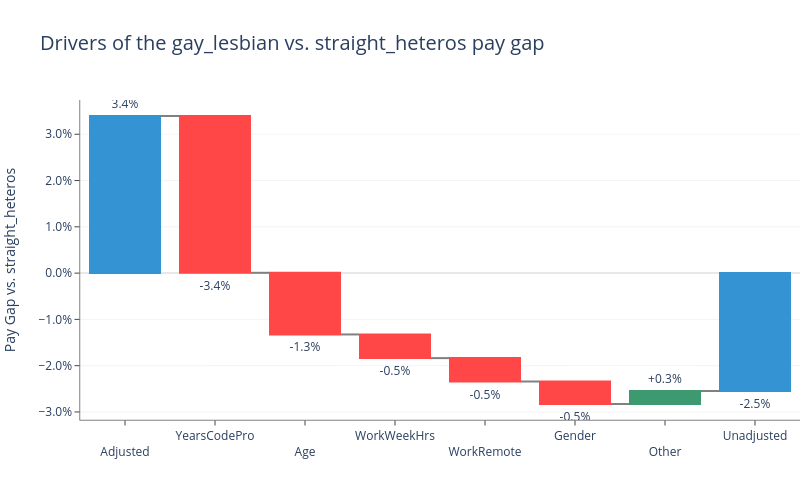

Starting at the adjusted / unexplained 3.4% premium, the lower average unadjusted earnings is largely accounted for by years of professional coding experience (a recurring theme) and age, suggesting that gay and lesbian developers are simply earlier in their careers than straight developers, on average.

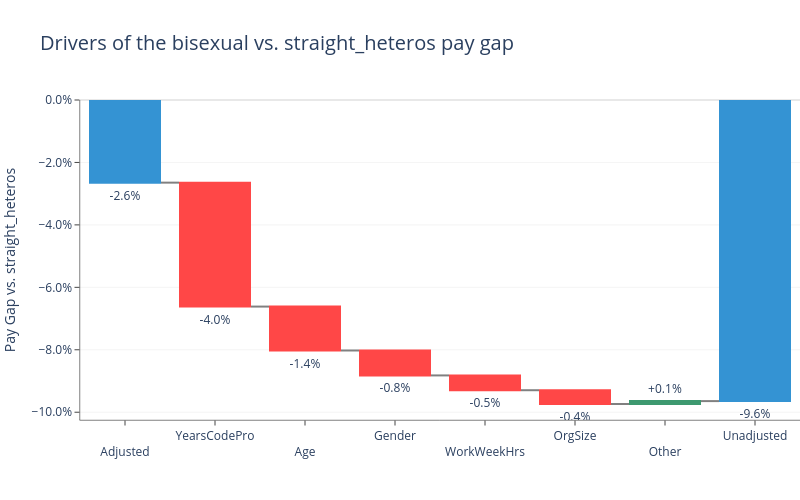

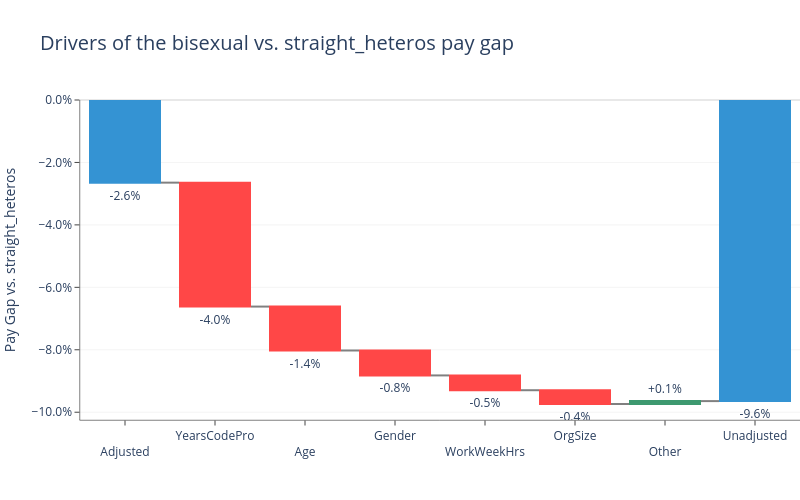

The decomposition of the difference in adjusted and unadjusted pay gaps is quite similar for bisexual developers. Professional experience and age continue to the do the most explanatory work here:

Parenthood

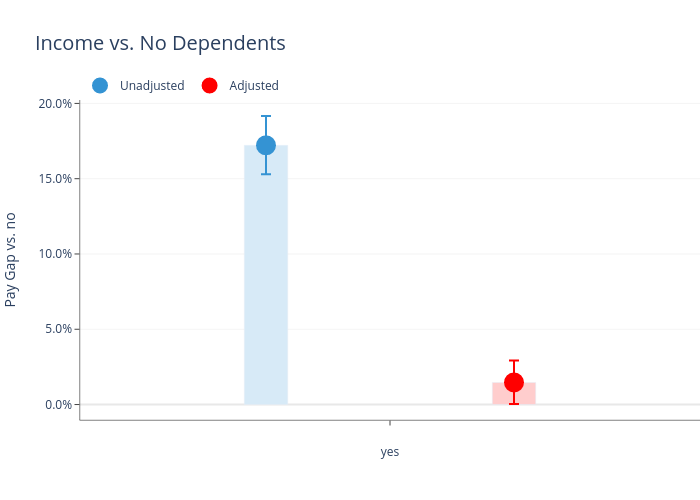

Parents earn more, but this is largely explained by other factors

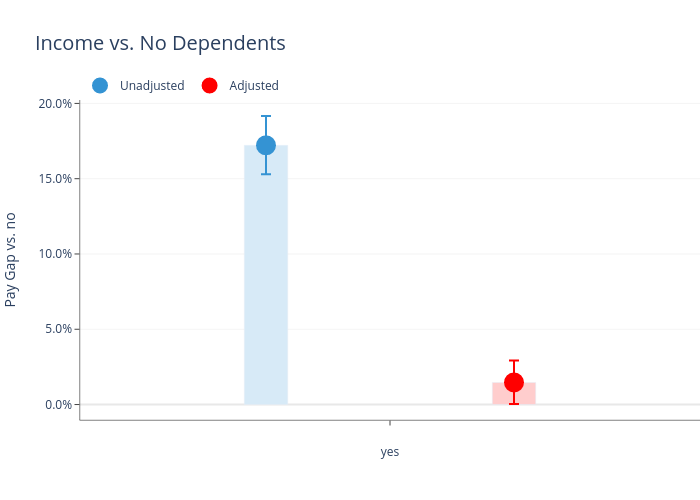

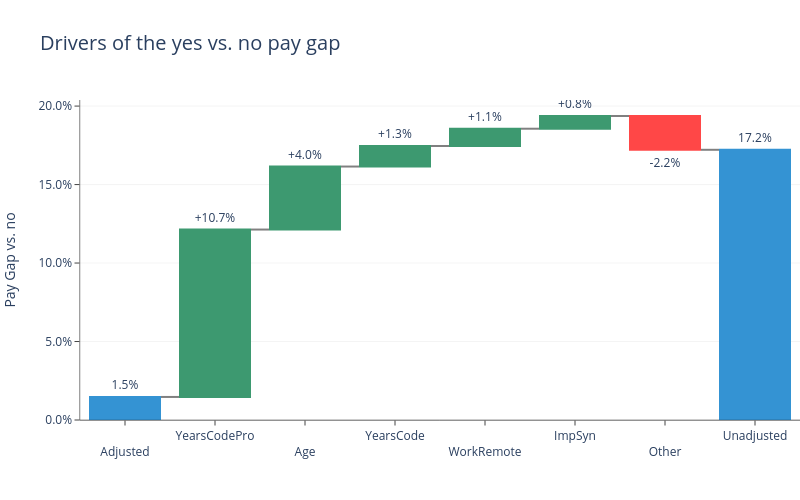

Software engineers with dependents (typically children) earn 17.2% more than those without, but this earnings premium can be almost entirely accounted for via the other factors described in this analysis.

Controlling for these variables reduces the parenthood earnings premium to 1.5%, which is small but statistically significant.

- Perhaps the data reflects that these developers earn extra income in order to take care of their

dependents

- Such a small bump in earnings like does not cover the additional expense of a child or other

dependent, however

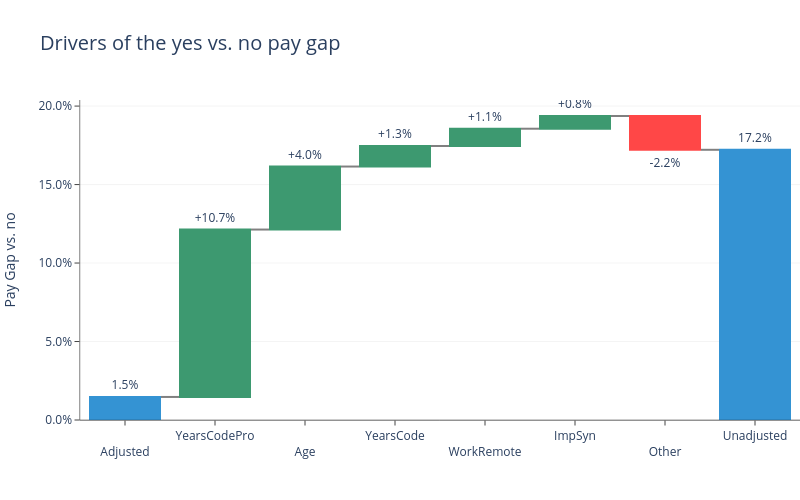

Unsurprisingly, years of software development experience and age account for most of the earnings premium among parents. These are largely mid and late career engineers.

Working remote explains another 1.1% of the pay premium among parents, as they are more likely to work from home, which makes sense given they may have a child to take care of.

Conclusion: Significant progress on pay

Not to editorialize, but I was encouraged by many of the results here. In general, along most dimensions, discrimination in software developer earnings appears small once various factors are controlled for. In most cases, the biggest factors were some combination of years of coding experience and age which are both “problems” that will largely fix themselves as the industry diversifies.

With the exception of race, most of the gaps are no more than a few percentage points in magnitude. In the case of race, the gaps are meaningful in some cases but difference is in fact in favor of minority groups like East Asian, South Asian, and Middle Eastern software developers. Their pay advantages are substantial, and the data from the Stack Overflow survey fail to fully explain these gaps.

The usual caveats to pay analyses apply here as well. Finding little discrimination on pay, after controlling for factors such as job title, does not disprove discrimination in its entirety.

- For example, if

female software engineers face discrimination in the form of reduced upward career mobility, that will not show up in this analysis, even though it depresses their earnings

- The same would apply to older software developers, who may be pressured out of their organizations to make room for cheaper, younger developers.

Analogous statistical caveats abound.

That said, the data suggest the software development industry is well on its way to pay parity across the important dimensions of age, race, gender, and sexuality.

Thanks for reading part 1 of my 2020 analysis of software developer pay. You can find the rest of the analysis and methodology here.